Data licences

A data licence is a legal arrangement between the creator of the data and the end-user specifying what users can do with the data.

What are data licences?

It’s great to publish - both data and articles - but releasing data without making the terms of use clear can be confusing and counterproductive, as it may deter potential users from using and citing the data. One of the most effective ways to communicate permissions to potential users of data are data licences.

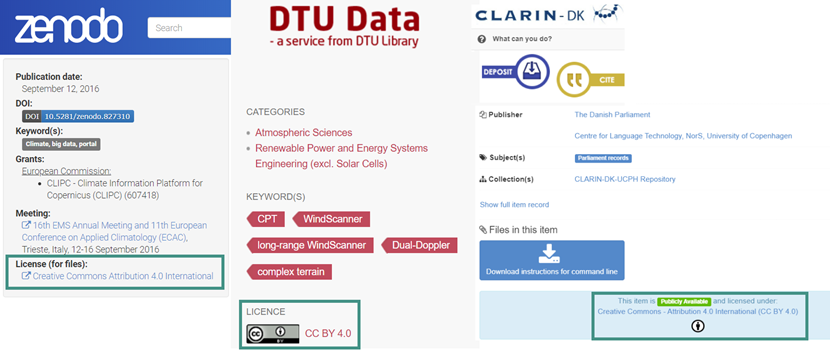

A data licence is a legal arrangement between the creator of the data and the end-user, or the place the data will be deposited, specifying what users can do with the data. Here are some examples of data licences at three different repositories.

Many institutions and public organisations have established repositories, where scientists can upload and share their data. Projects funded by the European Union are expected to make generated data or their metadata available to the public and attach a data licence - for example through data repositories.

The CC licences

The most commonly and widely used data licences are the suite of Creative Commons (CC) copyright licences which clearly describe how data can and cannot be reused. The CC licences are irrevocable. This means that once you receive material under a CC licence, you will always have the right to use it under those licence terms, even if the licensor changes his or her mind and stops distributing under the CC licence terms. Of course, you may choose to respect the licensor’s wishes and stop using the work, but once a dataset has been issued a CC licence, it cannot be revoked afterwards.

A scientific dataset, which other researchers may build upon or which is published together with a scientific article, is usually published under the CC-BY licence.

Do you want to keep the copyrights or share everything? Let’s take a closer look at the CC licences.

Attribution CC BY

Attribution CC BY

This licence lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work, even commercially, as long as they credit you for the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licences offered. Recommended for maximum dissemination and use of licenced materials.

Attribution CC BY-SA

Attribution CC BY-SA

This licence lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work even for commercial purposes, as long as they credit you and licence their new creations under the identical terms. This licence is often compared to “copyleft” free and open source software licences. All new works based on yours will carry the same licence, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. This is the licence used by Wikipedia, and is recommended for materials that would benefit from incorporating content from Wikipedia and similarly licenced projects.

Attribution NoDerivs CC BY-ND

Attribution NoDerivs CC BY-ND

This licence lets others reuse the work for any purpose, including commercially. However, it cannot be shared with others in adapted form, and credit must be provided to you.

Attribution NonCommercial CC BY-NC

Attribution NonCommercial CC BY-NC

This licence lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge you and be non-commercial, they don’t have to licence their derivative works on the same terms.

Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA

Attribution NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA

This licence lets others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, as long as they credit you and licence their new creations under the identical terms.

Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs CC BY-NC-ND

Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs CC BY-NC-ND

This licence is the most restrictive of these six main licences, only allowing others to download your works and share them with others as long as they credit you, but they can’t change them in any way or use them commercially.

Licence Version

In November 2013, Creative Commons published the version 4.0 licence suite. These licences are the most up-to-date licences offered by CC and are recommended over all prior versions. You should always indicate the version number of the licence you are issuing. You can see how the licences have been improved over time on the Licence Version page.

There are other licence types e.g. for software and code. See alternative licences in below guides.

- Alex Ball (2014), A digital Curation Centre and JISC legal "working level" guide - How to license Research Data

- Choosing a Licence, About CC Licences

- Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives (CESSDA) Training, Licensing your data

Copyright

In Denmark copyright protects literary and artistic works which include books, articles, films, photographs, pictures, drawings, computer programs, drama and music. Such works are subject to copyright protection lasting for 70 years after the death of the author. You can obtain this protection only if the work is original, that is, created by an author in a creative way.

Copyright also protects a number of things that are not, or at least not always, actual original works, but which nevertheless need protection. These include creative artists’ performance of works, sound recordings, films and photographs, whether they are original or not, TV shows, etc. They are subject to what is known as neighbouring rights protection. It is not a requirement that the product is original to obtain this protection, and the duration of the protection is substantially shorter than the copyright protection.

Is research protected by copyright?

Read more about it at Forskerportalen of the Committee for Protection of Scientific Work (UBVA).

Test your FAIR-ability here

Three quizzes on qualitative, quantitative and sensitive quantitative data will take you through example research situations, where the best practices for FAIR may clash with what is practical or possible in reality. Choose the quiz that is most relevant for you – or test yourself on all three.